Why is Urban Redevelopment so Difficult?

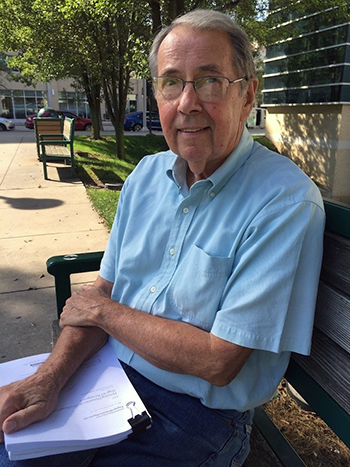

Noted housing policy scholar Thomas Bier presents the picture of urban/suburban interconnectedness

Since the 1950s, governments at all levels have been contending with urban decline. Now, what were new suburbs 60-70 years ago are also showing decline. And through it all, “the city” has continued to extend and sprawl outward into the countryside.

A new book by noted housing policy expert Thomas Bier, a senior fellow with the Maxine Goodman Levin College of Urban Affairs at Cleveland State University, describes how, over the decades, public policies combined with natural population migration shaped the city of Cleveland, Cuyahoga County, and the region.

“Basically,” Bier notes, “it’s been build new and abandon old.”

Housing Dynamics in Northeast Ohio: Setting the Stage for Resurgence provides a comprehensive review of housing development and population migration across the region. Particular attention is given to Cuyahoga County as it is the first county in Ohio to be nearly built out. With little vacant land remaining in its outer suburbs, the county faces a tax-base crisis unless large amounts of redevelopment and renewal are produced in the county’s old-core jurisdictions of Cleveland and inner suburbs.

“It represents an unprecedented challenge, but public policy is not oriented to support what is needed,” Bier says. “Rather, it is oriented toward building new suburbs while leaving old places to twist in the wind. It’s a consequence of the mindset cultivated by home rule: ‘You, jurisdiction X, are self-governing, so it’s your problem, you fix it.’ Each aged community is essentially on its own facing major needs for renewal and redevelopment. It’s do-It-yourself survival.”

The heart of the solution, Bier maintains, is tax-growth sharing. Since the region, not individual communities, creates economic expansion, tax-base growth, wherever located in the region, should serve to support renewal and redevelopment wherever needed. In time, all places age and need new life. Growth sharing would ensure that all have a reasonable chance for continuing economic viability and independence.

The book also raises a state constitutional issue. The Ohio Constitution declares that government is instituted for the equal protection of all, but that is far from what the state is doing for many property owners.

“By facilitating the development of new suburbs on rural land while doing little to support renewal and redevelopment of old places, the state is, in effect, taking property value from owners in old places and giving it to owners in new ones,” Bier adds. “The state is playing favorites.”

Bier argues that local and state officials need to work collaboratively to reimagine priorities and create a new legal framework that balances the renewal and redevelopment of aged communities with the construction of new ones.

“If Northeast Ohio is to realize its potential to flourish in its third century, practices and guiding policies must change,” Bier says. “And to some degree that surely applies to the other regions in the state.”

###